top of page

DESCARTES

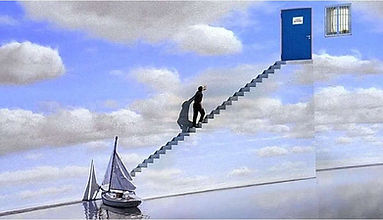

Aside from Plato's Cave, there might not be a more influential moment in the history of philosophy, or the history of cinema for that matter, than Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy.

And there are just too many amazing movies that wrestle with his ideas to pick from. So for this assignment, I'm going to ask you to read some Descartes, and then pick a movie from a list (they're all represented on the title screen above) to analyze.

First, here's a brief overview of the basic process Descartes went through in his little cabin in the woods...

Descartes asked a really simple question: Is there actually anything I can be absolutely 100% certain of? His meditation on this question led him basically through the following thought process:

1. You've probably heard the expression "Fool me once, shame on you; fool me again, shame on me." After all, if someone, or if any source of knowledge for that matter, deceives me, I should know better than to rely on it again. So he turns his attention from what he believes to the sources of his beliefs -- the epistemological (theory of knowledge) strategies by which he comes to believe anything, and tries to discern which are reliable and which are dubious.

2. He first divides sources of knowledge into two camps: those which rely on other people (including any sort of media -- indeed, the word "media" means to mediate between two things, in this case, between me and the world I'm trying to understand).

3. He quickly realizes that he really can't trust any source of knowledge that relies on other people, since they've deceived him so many times in the past. Remember: Fool me once, shame on you...

4. So that leaves himself, as the only reliable source of knowledge.

5. He further divides his own capabilities to acquire knowledge into two camps: knowledge gained empirically, through his senses, or body, and knowledge gained rationally, through his mind.

6. Now this is where it starts to get interesting and really relevant for film. Has his body/senses fooled him? Have they fooled all of us? Of course. Have you ever seen the sun rise or set? Of course you haven't -- the sun doesn't in fact rise or set. The earth tilts on its axis and it "looks" like it's doing so. Objects appear to grow in size as they approach and shrink as they recede. A stick placed in water appears to break. Since Descartes' time science has only deepened our appreciation of just how wrong our senses are -- the material world is made up of atoms, but atoms are themselves almost entirely made up of empty space. And yet, when we open our eyes, that same material world appears perfectly solid. In fact, the body sends us messages about the world that are false much more often than any other source of knowledge -- there is no greater deceiver than the body, and thus no greater shame than to be fooled by it again.

7. So, at this point, we can't be certain of any beliefs grounded in knowledge gained by other people, nor can we be certain of any knowledge gained by our senses. All that leaves is knowledge gained by our minds alone.

8. But let's pause to take a closer look at what knowledge we normally gain by our senses that we can no longer be certain of. But before doing so, it's useful to distinguish two forms of beliefs, specifically two forms of judgments: qualitative and quantitative, or predicative and existential. Qualitative judgements have three parts: the subject, the copula, and the predicate Consider:

THE ROSE IS RED

In this case, ROSE is the subject of the judgment/belief, "is" is the copula (it "couples" the subject and the predicate) and RED is the predicate, or quality of the subject.

EXISTENTIAL, or QUANTITATIVE beliefs on the other hand simply state the existence of a subject, that it exists and take the form "Subject is." In this case,

9. OK. So the thing is, we're dependent on our senses for both existential and qualitative judgments -- I can only know that the rose is red with my eyes, and I can only know that it even exists with my eyes as well. I mean, could I ever know that the rose is red or exists without relying on my senses or other people? Could I know that the earth is round without relying on my senses -- could I know that the earth even exists? Could I know anything about the material universe at all without relying on my senses? Could I even know that the material universe exists? Could I know that my body exists? Could I know that I exist? That anything exists?

THE ROSE IS

or

THE ROSE EXISTS

This is the impasse Descartes finds himself at by the end of Meditation I. Famously, in Meditation II, he makes a compelling case that at the very least, he can be 100% certain that he exists. His argument goes something like this:

1. I know I believe, or think, I exist -- I also believe or think the material universe exists. The problem is that I don't know if I'm right or wrong in those belief because I can't rely on my senses. But recall that he still can rely on his mind, on logic or rationality, as a foundation for beliefs. So if he can prove that he exists purely by logic, and thus purely with his mind, without relying at all on his senses, he will be able to know with 100% certainty that he does, in fact, exist. Let's take a look at that argument.

2. Qualitative Judgments logically imply Existential Judgments. That is to say, if it's true that the rose is red, it must be true that the rose exists. Something can't be something without being in the first place. A rose that isn't, isn't red, and a rose that is red, is.

3. OK, well let's apply that to Descartes. He knows he believes that he exists. He just doesn't know if he's right about that. He might be wrong. So one of two beliefs are true: either "I am right" or "I am wrong." Note that these are both qualitative judgements, and as qualitative judgments, they logically imply existential judgements, in this case, "I am, I exist." This is actually pretty monumental: in the end, it doesn't actually matter if he's right or he's wrong, since both of the Qualitative judgments "I am right" and "I am wrong" imply the same Existential judgment "I am." And thus, he famously concludes:

I THINK THEREFORE I AM

Now, there was a moment in the lead up to this conclusion that's of particular relevance for film, both on the level of content and form. When entertaining the possibility that he's wrong about the material world, and he himself, existing, he conjures up two powerful explanations that would lead him to his (and our) delusion: 1) Perhaps some "evil genius" (malie genie) is creating the illusion that I and the world exist; 2) Perhaps I am dreaming. After all, as he rightfully points out, we've all had dreams that were so realistic we didn't realize we were dreaming. So how could we be certain that we're not dreaming right now?

And as almost an aside, Descartes launched an obsession of science fiction film makers when he, attempting to illustrate his point that he can't trust his senses (and we can't trust ours), remarked that as he looked out his window he saw a man walking, but couldn't be absolutely certain that the man he was seeing wasn't, in fact, a robot..

INSTRUCTIONS

1. WATCH this video

2. READ Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy I and II OR LISTEN here

3. WATCH The Matrix or Inception or Total Recall or Vanilla Sky or Moon or Black Mirror's Striking Vipers or Black Mirror's Be Right Back or Blade Runner or Paprika or The Truman Show.

4. WRITE a 1-2 single-spaced page reflection on how the film you picked deals with Descartes' philosophy.

bottom of page